In the summer of 1864, John W. Garrett, President of the Baltimore & Ohio railroad, came to see General Lew Wallace. Mr. Garrett expressed concern for the safety of Washington (as well as his railroad). His personnel reported detachments of Confederate troops in the Shenandoah Valley. According to Garrett, such appearances preceded trouble. General Wallace decided to go to the western limit of his command, the Monocacy River, southwest of Frederick, Maryland. Upon his arrival at the blockhouse guarding the rail junction (Monocacy Junction) he found the country alive with rumor.

In the summer of 1864, John W. Garrett, President of the Baltimore & Ohio railroad, came to see General Lew Wallace. Mr. Garrett expressed concern for the safety of Washington (as well as his railroad). His personnel reported detachments of Confederate troops in the Shenandoah Valley. According to Garrett, such appearances preceded trouble. General Wallace decided to go to the western limit of his command, the Monocacy River, southwest of Frederick, Maryland. Upon his arrival at the blockhouse guarding the rail junction (Monocacy Junction) he found the country alive with rumor.A Rumor of War

Gossip indicated that a Confederate army, between 5,000 and 35,000 men strong, crossed the Potomac River on the 2nd or 3rd of July. Its exact whereabouts and destination were both unknown. General Wallace sent civilians to gather information. Confederate cavalry turned them away at every pass in the mountains west of Frederick. General Wallace believed this cavalry was screening a larger army.

Two miles north of the junction, a stone bridge called the Jug Bridge crossed the Monocacy, carrying the National Road that led to Baltimore. At the junction stood an iron railroad bridge and, a few hundred yards southwest of it, the wooden covered bridge of the Georgetown Pike, the road to Washington. Any invading army intent on Washington or Baltimore would have to come this way. After brief consideration, General Wallace believed that Washington was the objective. He began putting men in place.

The Battle of Monocacy

On July 9, 1864, 6,500 troops under the command of General Wallace met 14,000 battle–hardened veterans of the Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by General Jubal Early, on the farm fields near Monocacy Junction. Confederate troops held the field at day’s end, but Wallace and his men had delayed them long enough that reinforcements ultimately sent by Union General-in-Chief U.S. Grant would reach the lightly-defended U.S. capital just in time. Early’s plans to capture Washington failed. The battle of Monocacy is now known as the “battle that saved Washington.”

General Grant later wrote that Wallace had done more for the cause by losing this battle than many generals had accomplished by winning.

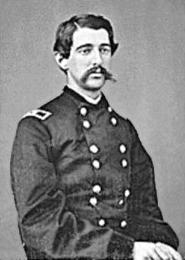

Colonel William Seward

As the Battle of Monocacy loomed, the city of Washington panicked. One of the men in Wallace’s small army was Colonel William Seward, son of Lincoln’s Secretary of State, William Henry Seward. Colonel Seward commanded the hard-fighting Ninth New York Heavy Artillery. Seward’s regiment fought in the middle of the battle. According to Wallace’s official report, the Ninth New York’s casualties totaled 102 killed and wounded with 99 missing, for a total of 201 casualties. Seward’s family, in Washington, received continuing reports from the battlefield. They knew about Wallace’s valiant defense and ultimate defeat.

The Secretary of State stayed at the War Department reading telegrams coming in from the battle until almost midnight. He had just returned home when Secretary of War Edwin Stanton arrived at the Seward residence to tell the family that there were reports that young William was wounded and taken prisoner. Attempting to learn the truth, Colonel Seward’s brother, Augustus, left early the next day to go to Baltimore. Augustus ultimately determined that his brother had been wounded, but not captured. Unfortunately, he couldn’t find him in the panic and chaos that gripped both Washington and Baltimore.

The Secretary of State stayed at the War Department reading telegrams coming in from the battle until almost midnight. He had just returned home when Secretary of War Edwin Stanton arrived at the Seward residence to tell the family that there were reports that young William was wounded and taken prisoner. Attempting to learn the truth, Colonel Seward’s brother, Augustus, left early the next day to go to Baltimore. Augustus ultimately determined that his brother had been wounded, but not captured. Unfortunately, he couldn’t find him in the panic and chaos that gripped both Washington and Baltimore.By that evening Lew Wallace telegrammed the Seward home: “I have the pleasure of contradicting my statement of last night. Colonel Seward is not a prisoner, and I am now told he is unhurt. He behaved with rare gallantry.”

While Colonel Seward was reported safe on July 10, Washington definitely was not. Jubal Early and his veterans marched on the city. On July 11, Early’s army arrived in front of Ft. Stevens, the northernmost fort in Washington’s defensive chain. Early could see the flag flying on the dome of the U.S. Capitol.

Danger to Washington, D.C.

Grant’s reinforcements had not yet arrived. As a result, the city was in jeopardy. For some reason, however, Early delayed his attack. Grant’s reinforcements arrived on the night of the July 11. Early’s men attacked on July 12. During this fighting, President Lincoln arrived at Ft. Stevens and insisted on watching the action from the ramparts. Lincoln’s actions exposed him to Confederate sharpshooters, who killed an officer standing nearby. At that point others convinced the President to move off the walls.

William Seward’s Wound

As it turned out, Wallace had relayed incorrect information to the Seward family. Colonel Seward had suffered a slight wound to his arm. Seward also broke his leg when his horse fell on him during the battle. Unable to walk off the battlefield, he only escaped capture when he found a mule. He used his silk handkerchief as a bridle and rode off the field ahead of the Confederates. Seward’s promotion to brigadier general arrived within eight weeks. He served throughout the remainder of the war.

A banker before the war, General Seward returned to a successful career in banking after his time in the military. He followed politics, supported charitable causes, and served as a director for a number of corporations. In addition, he participated in historical and patriotic societies until his death in 1920—over 50 years the battle that saved Washington, directly affected the outcome of the Civil War, and likely changed the history of the nation.

Many years later General Wallace encountered one of the Confederate commanders, J. B. Gordon, at a White House reception. Gordon told Wallace he was the only Yankee who ever whipped him. Wallace replied that, in the end, his men ran from the field. “In that sense you are right,” Gordon countered, “but you snatched Washington out of our hands.”

Sources: Shadow of Shiloh, Gail Stephens, Indiana Historical Society Press, 2010

Seward, Lincoln’s Indispensable Man, Walter Stahr, Simon & Schuster, 2012