Traveling the Circuit

Lew Wallace was an attorney by profession, although he did not particularly enjoy this career. His initial effort at passing the bar in the mid-1840s failed. His first exam, graded by Isaac Blackford, Chief Justice of the Indiana, was not successful; while his answers may not have been particularly appropriate, certainly his cavalier note at the end of the exam that he would rather be fighting in the Mexican-American War did not endear him to Justice Blackford.

When Wallace returned from his time of service in the Mexican-American War, he met and fell in love with Susan Elston. His interest in Susan created the need for a respectable career and Wallace again took the bar exam and this time he succeeded. Lew discussed his early law career in his autobiography, which was published posthumously. After a brief time in Indianapolis, he established his law office in Covington, Indiana for a couple of years before relocating to Crawfordsville.

In the mid-1850s, it was customary for attorneys to “travel the circuit” in pursuit of business and to try cases in front of travelling judges. This was a common practice across the country. In his Autobiography, Wallace wrote about this experience—especially discussing one particular attorney who captured his attention.

We reached the town about dusk and stopped at the tavern. The bar-room, when we entered it after supper, was all a-squeeze with residents, spiced with parties to suits pending, witnesses, and jurors. The ceiling was low, and we had time to admire the depth and richness of the universal smoke-stain of the wooden walls. To edge in we had to bide our time. Every little while there would be bursts of laughter, and now and then a yell of delight. At last, within the zone of sight, this was what we saw: In front of us a spacious pioneer fireplace all aglow with a fire scientifically built. On the right of the fireplace sat three of the best storytellers of Indiana, Edward A. Hannegan, Dan Mace, and John Pettit. Opposite them, a broad brick hearth intervening, were two strangers to me whom inquiry presently identified as famous lawyers and yarn-spinners of Illinois.

One may travel now from the Kennebec to Puget Sound and never see such a tournament as the five men were holding; only instead of splintering lances they were swapping anecdotes. As to the kind and color of the jokes submitted to the audience, while not always chaste, they never failed to hit home.

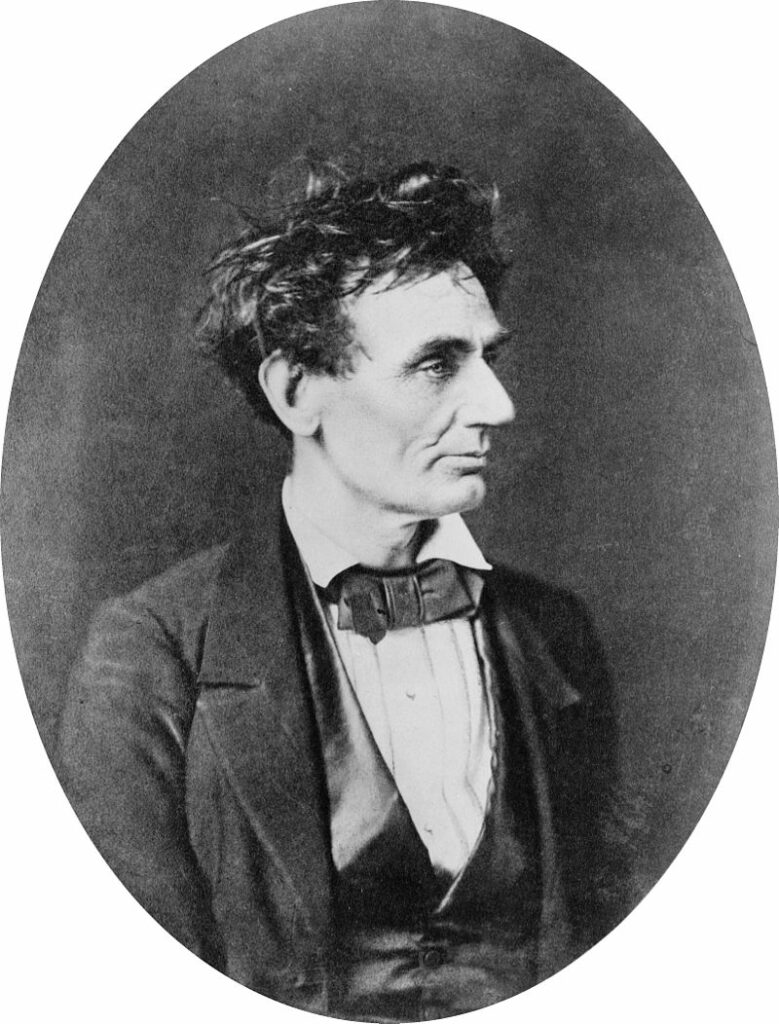

The criss-crossing went on till midnight, and for a long time it might not be said whether Illinois or Indiana was ahead. There was one of the contestants, however, who arrested my attention early, partly by his stories, partly by his appearance. Out of the mist of years he comes to me now exactly as he appeared then. His hair was thick, coarse, and defiant; it stood out in every direction. His features were massive, nose long, eyebrows protrusive, mouth large, cheeks hollow, eyes gray and always responsive to the humor. He smiled all the time, but never once did he laugh outright. His hands were large, his arms slender and disproportionately long. His legs were a wonder, particularly when he was in narration; he kept crossing and uncrossing them; sometimes it actually seemed he was trying to tie them into a bow-knot. His dress was more than plain; no part of it fit him. His shirt collar had come from the home laundry innocent of starch. The black cravat about his neck persisted in an ungovernable affinity with his left ear. Altogether I thought him the gauntest, quaintest, and most positively ugly man who had ever attracted me enough to call for study. Still, when he was in speech, my eyes did not quit his face. He held me in unconsciousness. About midnight his competitors were disposed to give in; either their stores were exhausted, or they were tacitly conceding him the crown. From answering them story for story, he gave two or three to their one. At last he took the floor and held it. And looking back, I am now convinced that he frequently invented his replications; which is saying he possessed a marvelous [sic] gift of improvisation. Such was Abraham Lincoln. And to be perfectly candid, had one stood at my elbow that night in the old tavern and whispered: “Look at him closely. He will one day be president and the savior of his country,” I had laughed at the idea but a little less heartily than I laughed at the man. Afterwards I came to know him better, and then I did not laugh.

This was not the last time Wallace and Lincoln would cross paths. At other junctures in the 1850s, Wallace would witness Lincoln’s ability to speak with impressive power and engaging creativity. In the 1860s, Wallace and Lincoln met or exchanged communications many times until Lincoln’s death in April of 1865. Wallace’s final contributions to Lincoln and his family included the organization of the first leg of the Lincoln funeral train from Washington D.C. to Baltimore and then his service as a judge on the military tribunal that tried the Lincoln assassins in the summer of 1865.

Museum’s Vision

The General Lew Wallace Study and Museum celebrates and renews belief in the power of the individual spirit to affect American history and culture.

Museum’s Mission

The General Lew Wallace Study & Museum is deeply committed to the protection and preservation of Lew Wallace’s legacy now and for generations to come.