On January 10, 1910, the United States Capitol hosted a stirring unveiling ceremony for the statue of General Lew Wallace in Statuary Hall. After an invocation, Lew Wallace, Jr., the general’s grandson, unveiled the statue. The crowd included members of Lew Wallace’s family, James Whitcomb Riley, and Senator Albert J. Beveridge. Indiana Governor Thomas R. Marshall formally accepted the statue on behalf of his state.

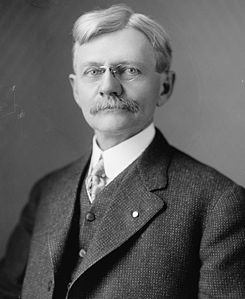

Thomas R. Marshall

Thomas R. Marshall knew Lew Wallace, as their paths had crossed many times—including the first time when they were on opposite sides of a lawsuit. Marshall was born in North Manchester in a politically active family in 1854. Four years later he attended one of the Lincoln-Douglas Debates and spent the debates sitting on the lap of either Abraham Lincoln or Stephen A. Douglas, depending on which man was speaking at the moment.

In 1869, at the age of 15 Marshall graduated from High School in Fort Wayne. His parents enrolled him at Wabash College. He joined Phi Gamma Delta fraternity. He did all he could to promote Democratic politics. When he graduated, he didn’t know whether he wanted to be a preacher or a doctor.

Marshall v. Wallace

A talented speaker and writer, Marshall took a job with the school newspaper, The Geyser. In 1872, during his final year, he wrote an unflattering column about a lady lecturer at the College. His column implied that she sought “liberties” with the boys in her boarding house. The lady did not take kindly to the inference. She hired Lew Wallace as her attorney and filed a suit for $20,000. Marshall fled to Indianapolis and hired the powerful attorney (and future President) Benjamin Harrison.

Harrison and Wallace were long-time friends. Ultimately, Harrison convinced the woman to drop her suit by demonstrating that the charges were likely true. He said she probably shouldn’t risk a public trial. When Marshall went to pay Harrison for his services, Harrison refused to charge Marshall. Instead, Harrison gave the young man a stern lecture on ethics and proper behavior.

Marshall went on to graduate at the top of his class. He was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. Like Lew Wallace (an honorary member of Phi Gamma Delta fraternity), Marshall maintained a strong interest in his alma mater. Also like Wallace, Marshall went on to join the Masonic Lodge. As a result of the libel case, Marshall grew interested in the law. He studied with different attorneys and quickly gained a wide reputation as a gifted orator.

Governor of Indiana

After some devastating personal losses in the early 1880s, Marshall drank heavily for a few years. With the support of his wife (she locked him in the house for two weeks) Marshall gave up drinking. He became an increasingly progressive Democrat and a Prohibitionist. His leadership in the Temperance movement propelled him into politics. On January 11, 1909 he took office as the 27th Governor of the State.

Marshall’s Speech

As governor and a personal friend, Marshall presided at the unveiling of the statue. He offered a lengthy and mellifluous oration extolling the virtues of Lew Wallace. With grand gestures he asked, “Do I attempt to paint the lily or to gild refined gold when I declare that the man who could do something in the hour of peace as well as in the hour of war to keep alive the traditions of the Republic is doubly blessed and doubly worthy of honor?” As the oration continued he went on to note, “If other States produce lawyers of renown, it stands of record in the courts of Indiana that Wallace was opposing counsel to Hendricks, Harrison, Morton, McDonald, and Turpie.” The orator neglected to point out that in his opposition to Harrison, Wallace was suing a young Thomas Marshall!

After a speech that included references to the greatness of Greece and Rome, the “flaming spirit of patriotism,” “Divine destiny,” the Apostle Paul, Count Egmont, Napoleon, Goldsmith, Jefferson, the Divine Comedy and Paradise Lost, Demosthenes, Achilles, and Themistocles, Marshall wound down. He said, “. . .it would have been necessary for Lincoln to have waded through slaughter to a throne and to have shut the gates of mercy on mankind. Here he waded through slaughter only to a cross and opened wide the gates of mercy to mankind.”

After great applause, Marshall’s finishing comments recognized the statue of Wallace, stating: “. . . the statue of a full-orbed man, the rays of whose life were shed not only upon things temporal, but upon things spiritual; the rays of whose life helped to bring to fruition human freedom; and the rays of whose life are helping still to bring to fruition Divine compassion.”

After the final applause, Marshall introduced James Whitcomb Riley and the program continued.

Vice President Marshall

Just two years after this speech, Marshall’s leadership in the Democratic Party and Indiana’s critical role as a swing state led to his nomination as vice president on the Democratic ticket with Woodrow Wilson. While the two were successful in the election, they had very different personalities which led to Wilson limiting Marshall’s activities. Marshall went on to play an enormously important role in the Wilson administration as President of the Senate in the months leading up to World War I. As a gifted orator, he travelled the country during the War.

In the wake of Wilson’s stroke Marshall took over many of the public duties of the president. However, Marshall was prevented from seeing Wilson for the rest of his term. Rather than force a constitutional crisis, Marshall refused to fight Mrs. Wilson and the few close advisors visited the president. Marshall did not see the president until the last day of Wilson’s administration.

A Sense of Humor

After the end of the Wilson administration, Marshall returned to his law practice in Indianapolis and travelled widely. For all of his support of a progressive agenda, Marshall is best remembered for his wit. He told a joke about a woman with two sons. One son went to sea. The other was elected vice president. Neither was ever heard of again.

After the end of the Wilson administration, Marshall returned to his law practice in Indianapolis and travelled widely. For all of his support of a progressive agenda, Marshall is best remembered for his wit. He told a joke about a woman with two sons. One son went to sea. The other was elected vice president. Neither was ever heard of again.

On hearing of his own nomination as vice president, he announced that he was not surprised. “Indiana is the mother of Vice Presidents; home of more second-class men than any other,” he said. After his election as vice president, he sent Woodrow Wilson a book, inscribed “From your only Vice.”

Perhaps Marshall’s most famous quip came during his service as President of the Senate when, in response to Senator Joseph Bristow’s catalog of the nation’s needs, Marshall leaned over and quipped the often-repeated phrase, “What this country needs is a really good five-cent cigar.”

1920 Presidential Election

Some briefly considered Marshall for the 1920 presidential nomination. However, Marshall threw his support behind James Cox for president and Franklin Roosevelt for vice president. The Republican team of Harding and Coolidge won. Afterwards, Marshall sent a note to Coolidge, offering “sincere condolences” for his misfortune in being elected vice president.

A Long-Standing Friendship

The Wallace family maintained a friendship with Marshall over the years. In 1925, Lew Wallace, Jr. contributed some thoughts to Marshall’s autobiography Recollections of Thomas R. Marshall: A Hoosier Salad. Wallace he noted, slightly tongue in cheek, “I first knew Marshall when Governor of Indiana—not too impressive then. He grew in stature as no other man, in politics, and public life, with whom I had some associations. There was something very “home spun” in his innate characteristics and growth that was very wholesome and appealing. He was often “the wise man for salt” in his ‘perfect salad.”

Andrew O’Connor made the statue of white marble. Henry Wallace, Lew’s son and the father of Lew, Jr. so liked this statue that he asked the sculptor to make a bronze replica. After 100 years, this bronze version continues to grace the grounds of the Lew Wallace Study.