“My God, did I set all of this in motion?”

–Lew Wallace

Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ by General Lew Wallace was published by Harper & Brothers on November 12, 1880. Wallace had been researching and writing the novel for seven years. He did most of his work underneath a beech tree near his residence in Crawfordsville, Indiana.

The novel grew in such popularity during Wallace’s lifetime that it was adapted into a stage play in 1899. That dramatization was followed by the motion picture productions in 1907, 1925, 1959, and 2016. Ben-Hur has also been adapted into several cartoons and a musical.

Ben-Hur‘s impact on American culture is larger than the dramatic adaptations alone. The Supreme Tribe of Ben-Hur, a national fraternal organization founded upon Ben-Hur, later reformed into Ben-Hur Life Insurance. There have even been American towns named after Ben-Hur.

“It seems now that when I sit down finally in the old man’s gown and slippers, helping the cat to keep the fireplace warm, I shall look back upon Ben-Hur as my best performance…”

The Novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ

Following his first novel, The Fair God (1873), Lew Wallace believed he could make a career for himself in writing. Although a novel with Jesus Christ as the protagonist would be a hard sell with the American public, Wallace began writing.

He framed the tale through the eyes of a young Jewish noble, Judah Ben-Hur.

The novel featured friendship, betrayal, revenge, love lost, love regained, redemption, and, of course, a chariot race.

In a preface to “The First Christmas,” Wallace recounts some of the process of writing Ben-Hur, including a conversation with noted agnostic Robert G. Ingersoll. Wallace wrote most of his masterpiece underneath a beech tree in Crawfordsville, Indiana. He completed the final chapters of the novel, especially those dealing with the crucifixion of Christ, while he was serving as Governor of the New Mexico Territory.

Ben-Hur was an unusual novel for its time. Literature had moved away from historical, romantic, adventure fiction; the new trend was to write realistic fiction about contemporary life. However, Ben-Hur created a resurgence of its literary type. Henry Sienkiewicz’s Quo Vadis? is the best example of a popular novel whose author found inspiration from reading Ben-Hur.

The juggernaut Harper & Brothers greatly aided sales of Ben-Hur through its distribution and advertising policies, particularly by including excerpts in school readers. School readers were the major product of most publishers; including an excerpt of the sea battle or the chariot race from Ben-Hur piqued students’ interest enough to buy the novel or at least check it out from the libraries, which often listed Ben-Hur among their most requested books. The novel has never been out of print since its first printing in 1880.

Download the Preface to “The First Christmas” by Lew Wallace.

Stage Adaptation

Lew Wallace doubted Ben-Hur would translate into a successful stage adaptation. He anticipated two problems in particular. First was dealing sensitively with the religious nature of the book and the problems with an actor portraying Jesus Christ. The second problem was how to portray a chariot race in a theater.

Lew Wallace doubted Ben-Hur would translate into a successful stage adaptation. He anticipated two problems in particular. First was dealing sensitively with the religious nature of the book and the problems with an actor portraying Jesus Christ. The second problem was how to portray a chariot race in a theater.

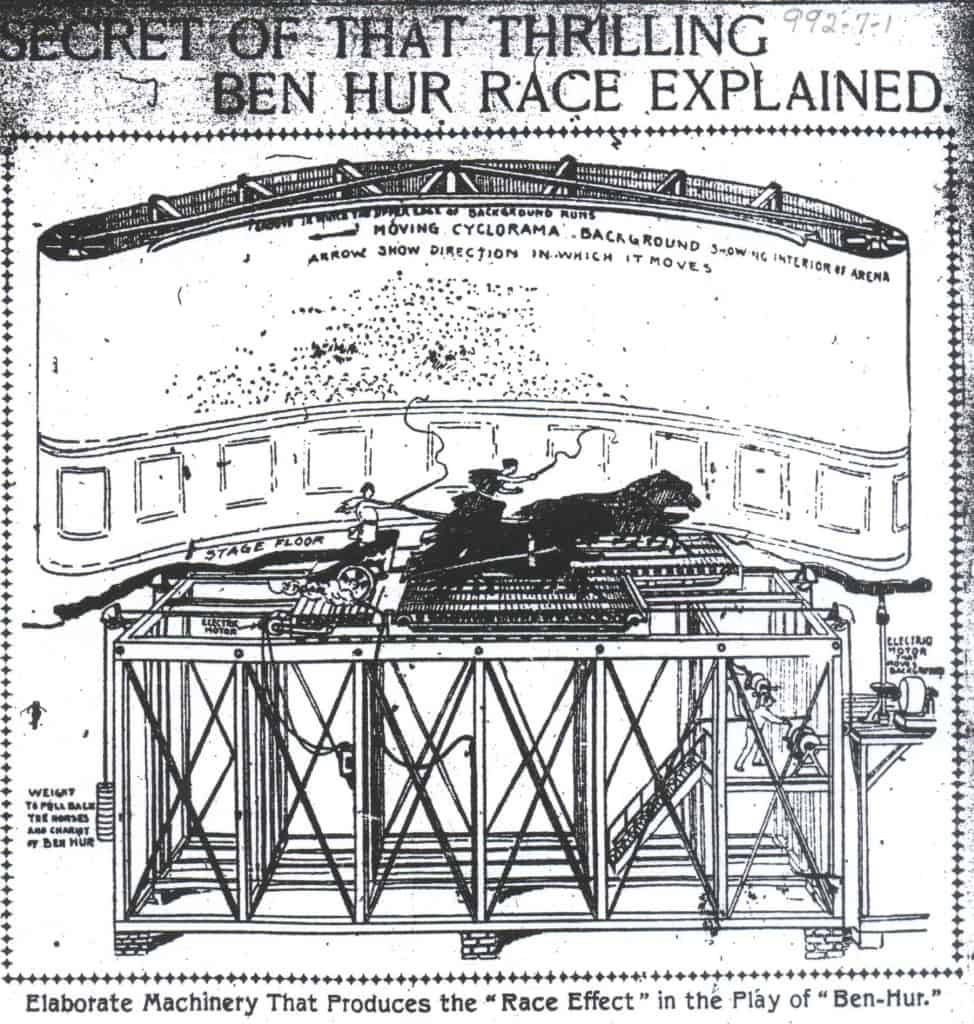

Stage magnates Marc Klaw and Abraham Erlanger managed to convince Wallace otherwise. They promised to depict Jesus Christ only as a beam of white light. They solved the problem of the chariot race by training eight horses, pulling two chariots, to run on treadmills installed in the floor of the stage. While the horses ran at full gallop on the stage, the background scenery–installed on a cyclorama–moved behind the racing chariots to complete the illusion that the chariots and horses were actually moving.

Ben-Hur on Broadway

Ben-Hur opened at the Broadway Theater in New York City on November 29, 1899. William Young adapted the novel for the stage. Joseph Brooks directed. Edward Morgan was the first Judah Ben-Hur on the stage, although William Farnum soon replaced him. William S. Hart, who would later achieve fame for his roles in silent westerns, portrayed Messala on opening night.

Ben-Hur took to the road and often held two-week engagements in U. S. cities. The production also appeared in Europe and Australia. Estimates suggest there were over 6,000 performances given and over 20 million people saw Ben-Hur during its twenty-one-year run. The final performance of Ben-Hur was delivered in April 1921.

1907 Movie

In 1907 a “moving picture” company known as Kalem decided to film Ben-Hur. This first incarnation of Ben-Hur on film was fifteen minutes in length and was in no way comparable to the motion picture spectacles that would follow. Kalem viewed the production as inexpensive and hoped to turn a quick profit, due to the phenomenal success of the book and stage play. However, Kalem neglected to seek permission from the Wallace estate, Harper & Bros. (publishers of Ben-Hur), or Klaw & Erlanger (producers of the stage play) to adapt the work into a motion picture.

Henry Wallace, Lew Wallace’s son, learned of this unauthorized version of Ben-Hur when the film appeared in “cheap five cent theatres” in Indianapolis. He promptly fired off letters to interested parties such as Harpers and Klaw & Erlanger. In one letter, Henry wrote, “I can see the finish of the play unless a quick and hard move is made on this form of entertainment. The people will be surfeited with the name no matter how poor the scenes.”

Lawsuit

Shortly thereafter, Henry Wallace, Harper & Bros, and Klaw & Erlanger brought suit against Kalem. They charged that Kalem had violated the copyright existing on the book. Furthermore they argued that the film cut into the profits of the stage production–not because it was strong competition against the stage play, but because the shoddy film cheapened the artistic integrity of Ben-Hur. Kalem, on the other hand, argued that the film would serve as good publicity for both the book and the play.

On November 13, 1911, the United States Supreme Court decided in favor of the plaintiffs. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. delivered the opinion of the court, which upheld the lower court’s ruling [Kalem Co. v. Harper Bros., 222 U.S. 55 (1911)]. The court ordered Kalem to pay $25,000 in damages, which was likely more than it even cost to produce the film. Due to Henry Wallace’s foresight, he was ultimately responsible for securing the intellectual property of authors from copyright infringement by film and theatrical productions.

Ben-Hur Film Rights

When Henry Wallace was asked to sell the film rights to his father’s literary works, he responded, “I will oppose in every way possible all attempts to produce any of General Wallace’s work in moving pictures. The reason is because the average moving picture shows are wretched exhibitions utterly unworthy of dignified consideration.”

When Henry Wallace was asked to sell the film rights to his father’s literary works, he responded, “I will oppose in every way possible all attempts to produce any of General Wallace’s work in moving pictures. The reason is because the average moving picture shows are wretched exhibitions utterly unworthy of dignified consideration.”

However, in 1915 Henry witnessed D. W. Griffith’s masterpiece Birth of a Nation. Perhaps the memorable “Ride of the Klan” scene convinced him that Ben-Hur‘s chariot race could be filmed equally well. Henry affixed a price tag of one million dollars for the movie rights. At this price no one was willing to pay. However, on August 2, 1921, Henry lowered his demands and settled on $600,000 for the rights to Ben-Hur. By comparison, the most expensive movie made to that date was Intolerance, which cost one million dollars.

1925 Movie

A group headed by Abraham Erlanger acquired the film rights. (Erlanger was also responsible for bringing Ben-Hur to the stage.) Eventually the rights passed to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Filming began in Italy, but production delays and political upheaval convinced MGM studio head Irving Thalberg to return to the states. California had to substitute for the ancient Roman Empire.

Fred Niblo directed the film. William Wyler, who would re-make the story in 1959, was an assistant director. Ben-Hur was a breakout role for 25-year-old Ramon Novarro who, only three years earlier, had his first starring role. Francis X. Bushman played Messala. Many Hollywood stars flocked to the stupendous set and served as chariot race extras, including Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Harry Lloyd, Myrna Loy, and Lillian Gish.

For some, the 1925 chariot race might be better than the 1959 version. Stunt men participated in an actual race, with a monetary reward to the winner. In this way, the 1925 race provides more excitement and realism than the later, largely choreographed, version.

The film ended up costing MGM approximately $4 million dollars and was one of the most costly films of the silent era. It opened on December 30, 1925, at the George M. Cohan Theater in New York City and received rave reviews. After expenses, the film only turned a slight profit; nevertheless, it helped solidify MGM’s reputation as a major studio.

1959 Movie

With the advent of television into many American homes in the 1950s, many theaters closed and movie studios suffered. MGM decided to return to Ben-Hur in an effort to emerge from their financial difficulties.

With the advent of television into many American homes in the 1950s, many theaters closed and movie studios suffered. MGM decided to return to Ben-Hur in an effort to emerge from their financial difficulties.

William Wyler, who had already earned two Academy Awards® for best director, was selected to direct the film. British actors played Romans and American actors, for the most part, played the Jewish characters. Charlton Heston played Judah Ben-Hur and Stephen Boyd opposed him as Messala. Wyler chose to film in both Italy and California, following the example of the 1925 production.

Despite some lobbying from Crawfordsville, Indiana, residents to host Ben-Hur’s premier, it opened on November 19, 1959, at the Lowe’s State Theater in New York City. Ben-Hur’s initial release grossed in excess of $40 million.

Lasting Impact

The 1960 Academy Awards® presented Ben-Hur with eleven of twelve awards for which it had been nominated. The major categories, Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Actor, were all won. Curiously, the only category for which it was nominated but not awarded was Best Screenplay. This faux pas was largely the result of confusion and controversy over who had written the script. Although Karl Tunberg received credit for the screenplay, other writers, including Gore Vidal, had also worked on the script. Many attributed the initial screenplay to Christopher Fry, but due to a falling out he did not receive credit. Nevertheless, as Charlton Heston delivered his acceptance speech for Best Actor, he made certain to thank Fry for the screenplay.

The 1959 Ben-Hur is a cultural icon. It has become an American tradition to broadcast Ben-Hur over Easter weekend. In 1998 the American Film Institute listed Ben-Hur as one of the 100 Greatest Movies.

2016 Ben-Hur

On August 19, 2016, yet another theatrical release of Ben-Hur hit the screens. The movie starred Jack Huston as Judah Ben-Hur, Toby Kebbell as Messala, and Morgan Freeman as Sheikh Ilderim.

Timur Bekmambetov directed the movie and chose to film in Italy. The movie cost $100 million to make. During its opening weekend, it grossed only $11 million in the United States. Most secular critics panned the 2016 “re-visioning” of Ben-Hur. Christian reviewers viewed the film more favorably, but it ultimately proved a disappointment.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is the copy of Ben-Hur I have worth anything?

The value of an antique book depends on its availability and condition. A museum cannot ethically give an appraisal of a book. To determine the value of your book, take it to a reputable used or antique book dealer.

Where is the Ben-Hur manuscript?

The Lilly Library of rare books and manuscripts owns the Ben-Hur manuscript. The Lilly Library is located on the Indiana University campus in Bloomington, Indiana.

I heard someone was killed during the making of Ben-Hur.

See what snopes.com has to say about this question.

What inspired Lew Wallace to write Ben-Hur?

Lew Wallace answers this question in various articles, speeches, and other of his writings. In 1876, after a conversation on a train with a well-known agnostic, Col. Robert G. Ingersoll, Lew Wallace realized that he didn’t know as much as he would like to about his own faith. (He attended the Methodist Church off and on throughout his life, but considered himself indifferent to religion.) He thought that the idea of doing research for a book he could write would be the best motivation for him to tackle reading the Bible.

Lew had already written a short story describing the journey of the wise men to Bethlehem–a subject which had fascinated him since he was very young. This became the first book of Ben-Hur, with the rest of the novel describing the “religious and political conditions of the world at the time of the coming,” as he says in his Autobiography.

Was Lew Wallace a Christian?

Although Wallace was indifferent to religion before writing the book, he says in the preface to “The First Christmas,” 1899, that the act of writing resulted in “a conviction amounting to absolute belief in God and the divinity of Christ.” For Lew Wallace’s answer to this question in his own words, read the Preface of The First Christmas or the excerpt from his Autobiography “How I Came to Write Ben Hur.”

Ben-Hur Lectures

Over the years we have been fortunate enough to have Dr. Howard Miller deliver several lectures on various aspects of the Ben-Hur phenomenon.

A dynamic speaker and award-winning educator, Dr. Miller is a leading scholar on Ben-Hur and Lew Wallace’s life. A native Texan, he taught at the University of Texas at Austin for forty years, retiring in 2011. During his time at UT Austin, he was instrumental in founding the university’s department of Religious Studies. He was the recipient of several awards for teaching excellence. He has been involved with the General Lew Wallace Study & Museum since 2000 and is a regular Title Sponsor for the museum’s annual TASTE of Montgomery County fundraiser.

Videos of Dr. Miller’s lectures are available at the links below.

Redeeming Messala: Ben-Hur Beyond the 1959 Epic

The 1959 Ben-Hur: A New Tradition Begins

The 1925 Ben-Hur: Epic End to an Era

‘The Sacred Circus'” Ben-Hur on the Stage and on the Rails

Religious Conversion in Ben-Hur

Blog Posts about Ben-Hur

Our blog has several informational posts about aspects of the novel and films. To read through those posts, visit the Ben-Hur category page of our blog.